You Should Read Howard Zinn

Charles Dickens, teachers, and attentiveness might just save our history from ourselves.

I once was on a date with a young man who asked me what I was reading. I love this question. In the past, my answers were typically dominated by the fiction genre, in which characters talk to fiery angels, the hero’s journey is traversed on other planets, or where things end deliciously, unrealistically happily, and neatly. Who doesn’t like this kind of ending?

Thinking to share with him that evening such a treasured read, I found myself instead struggling to come up with a good fiction novel to share. The truth is that in recent years I have had to fight those gorgeous fiction books, as the burning questions of the reality I inhabit have dominated my reading for the last three years. So I tell him what I have been reading. I tell him about the gripping non-fiction that answers questions like How will we parent in climate catastrophes? What is racism and how does it affect American society? Are women considered humans in legislation regarding x, y, and z? How do American Oil Corporations affect the economy?

He finds this amusing. He tells me he doesn’t care for politics or any of this. He tells me about the vacation he is planning. It sounds a lot like the trips my friends and I take, the kind of blissful adventures that we can have no matter what the economy is up to, whether the climate is warming, or who sits in the president’s office. It hits me, as I sit there, how much of my life and my closest neighbors’ lives remain virtually unaffected by the machinations of society. The culture and political wars wage on, and the outcomes, either way, seem to barely register in our day-to-day. I think about the people I have been reading about. Scientists who are mothers. Economists with families locked into class systems they can’t break out of. Journalists who have adopted children. I think about what they show me, the ways a single piece of legislation can undo an entire American life. How the difference between a dream and a nightmare is one slight, critical detail. I think of the people in my life who I love, who brag about how little news they know or follow, who can afford to ignore the stories that upset them. All of this feels deeply unfair. It is deeply unfair.

Last week, Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved faced another round of calls to ban it. The themes are considered upsetting. One day I will write about how I almost dropped an English class to avoid being influenced by it. I am glad I didn’t. Slavery is upsetting. The aftermath of slavery is also upsetting. Morrison chooses one world undone, one single upset. She focuses our attention on a woman. The novel pays attention to the deeply unfair world this Sethe character lives in and how she responds to it. It is uncomfortable. It is a novel to share and keep passing around because it is brilliant and beautiful in its attention to someone’s humanity. It quietly reminds us of all the ways our stories–known and unknown–haunt us and the people around us.

When I was nine, I ambitiously started and quickly failed to read the entire Encyclopedia Britannica. Later I would spend hours on the web version, and then even later years would find me dragging their Great Works collection upstairs. I had this nagging fear that outside the world was far more complicated than my life let on. I felt unbearably young and ignorant. I wanted to know everything about everything. And if I could not know it, I wanted to know what I did not know.

Isn’t this why we pick up other people’s stories? Isn’t this what made Charles Dickens so popular? The Great Works collection loves Charles Dickens. Tons of students each year are asked to study carefully his words and write essays about what we think he was trying to tell us. Dickens is unquestionably a dominant force in English Literature. Great Works indeed.

His writing captures our hearts every Christmas with A Christmas Carol. He shatters those same hearts with A Tale Of Two Cities. Dickens, still speaking after death, tells us deeply human stories about people who in every iteration -from the animated films to the reimagined Italian versions- connect and move us. This humanity is larger than the moment it was written in, but the stories are undoubtedly about specific people, in a specific time and context. Dickens is after all a Victorian, British writer. This identity matters. He always tells stories in context. He pays attention to the little things. Zooming a hundred or so years in the future, there is a scene in Greta Gerwig’s 2017 film LADY BIRD where the young woman of the same name is discussing her college application essay. Lady Bird is dying to get out of her childhood town of Sacramento. The advisor, who happens to be a nun, tells Lady Bird that she loves this city. Lady Bird scoffs. She does not. The nun points out that this is evident in the way she writes about Sacramento. Lady Bird explains that her writing merely describes Sacramento; she doesn’t love it, she just paid attention to it.

“Don't you think maybe they are the same thing? Love and attention?” The nun counters.

In David Copperfield, Dickens fixes his attention on some simple and poor people who, despite a prevailing Victorian belief at the time had every ounce of nobility and character within them. Dickens names wealth and power as mere resources, not monopolies and inherent claims to righteousness and goodness. Kindness, strength, love, happiness, and nobility are for everyone, not simply the rich. Dickens loves the simple and the ordinary person. He pays attention to the citizen just trying to make a living in a social and economic system that favors the landowners, the wealthy, and the powerful. This care is infectious. We readers also love Copperfield. We also fix our attention on the people who pay the price for the social systems of the day, and we care about them (please do yourself a favor and watch the Armando Iannucci version of David Copperfield. Among other artistic choices of note he cast the most gorgeous man in the world, Dev Patel, bless).

Charles Dickens the writer cannot be separated from Charles Dickens the social critic. Dickens evaluated the stories British citizens told about each other. He exposed beliefs, values, and social choices and their impact on humans through his stories. This does not weaken the value of his storytelling. It strengthens it. He invites us to look at what is, and ask ourselves if this is the best we can do for each other. We are invited to pay attention to the people whose lives are affected, changed, moved, and broken apart by the people who have power. It is hard to give undivided attention and not fall in love, or at least be moved to care.

I think sometimes it’s hard to get into our history because the way it’s presented makes it difficult to care. Our attention is sharply focused on the biggest dates and events, the more human details and stories swept aside in a frantic rush to ace the AP test, the midterm, or just get to the end of the semester. I found someone who knows the importance of those events and dates and the human details within them. Howard Zinn wrote a book you really should read. It’s called A People’s History Of The United States. It’s biased, of course, because like all history writers, Zinn makes a choice. He chooses to give his undivided attention to the people of America. He writes a ground-up history of the facts, the ideas people had, and the ideas they made American law and society out of. Zinn looks at the ideas that built this place. And he looks at the facts of how those choices, a lot of them made by people who owned land, power, votes, influence, and other humans, impacted everyone else. It’s a fascinating, drama-filled, deeply human account. Some people find this upsetting. It can be upsetting that history is deeply unfair at times. But these inequalities or disparities are worth our attention whether they affect us or not. We must know ourselves in context.

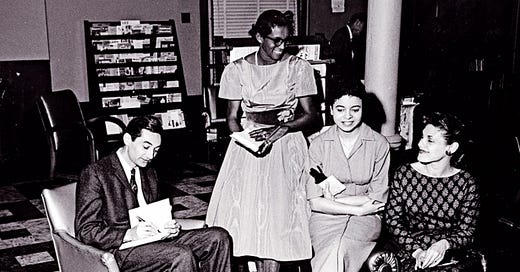

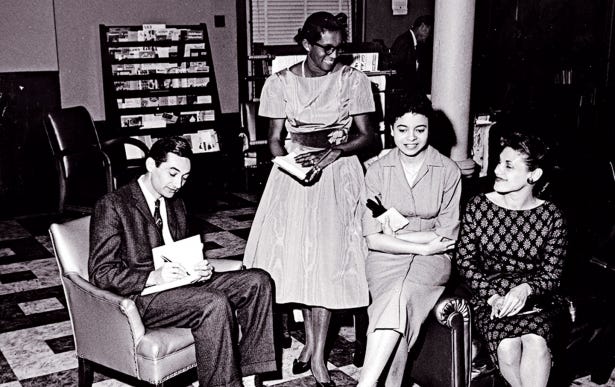

Zinn died in 2010 of a heart attack. The life he led and the work he left behind touched millions of people throughout his lifetime. He was an educator, a WW2 Air Force veteran, a shipyard worker, a civil rights activist, playwright, historian, father, and son of Jewish immigrants. He was an American man who paid attention. You can’t miss in any of his writing the indelible impact of his many experiences up close and personal with other Americans. Zinn broke his young back working in the shipyard, dropped the napalm in France as a Bombardier, and fought fascists in the US Air Force. He earned his undergraduate, master’s, and Ph.D. degrees as a young married man and father working in warehouses. He lived in public housing in the city of New York. In the 1950s he chaired the history department at Spelman College, a historically Black college for women, and took part in the student protests. He was fired for that. Zinn kept advocating for civil rights, documenting carefully the history unfolding around him. He kept notes of interviews with civil rights leaders, fought for voting rights in the south, and witnessed and documented the march on Selma.

Zinn’s attention throughout his life was on the plight of Americans who lived under ideas of white supremacy and other forms of oppression. He taught political science at Boston University and took part in African American-led anti-war movements. He wrestled his whole life with the repercussions of his actions in World War 2. He wrote and spoke about this. Howard Zinn was an American citizen who concerned his writings, his teaching, and his work with American ideas and what those ideas meant to other people. His close experiences with labor workers, Black women, civil rights organizers, and students changed how he lived and taught. This matters.

Born in 1922 to working-class parents, Zinn grew up with few books. The only books he could afford were procured through a dime and coupon system his parents discovered. They didn’t realize the coupon system was valid for volumes of the complete works of Charles Dickens. Young Zinn inadvertently ended up with twenty volumes of the master’s writings.

“I knew that a historian (or a journalist, or anyone telling a story) was forced to choose, out of an infinite number of facts, what to present, what to omit. And that decision inevitably would reflect, whether consciously or not, the interests of the historian.”

― Howard Zinn, A People's History of the United States

I like to think that Dickens’ sharp eye for civil hypocrisies and social customs inspired Zinn to look at his society with open eyes. While Howard Zinn’s work is about history and fact, it is indeed presented through his radical lens. It is considered radical, in historical settings, to think about the lives of women, children, Natives, and poor people concerning the law. It is considered radical to look at the laws created to enforce ideas of racial superiority. Or how and for whom the American economy or military war complex is set up for. Zinn describes the facts and the impact of our social systems and the events that made them.

Some people think that this description and recounting of facts should be dismissed wholesale because of Zinn’s thoughts about what should be done in response to those facts and history. Zinn’s socialist beliefs are not secret, but this book, A People’s History of The United States, is not concerned with centering his personal beliefs about what should be done. It’s about the beliefs that built this country, and the ongoing push and pulls of American society. When we look at the Florida Black Heritage Trail, we find a history of people who responded in a lot of different ways (like Zinn) to the culture they found themselves in. Zinn wrote this book because there were no overarching, credible history textbooks written that looked at American history as a people’s history, instead of a state’s history.

Zinn was aware of his humanity and viewpoint. Like Dickens and Lady Bird, he also chooses his objects of attention. He knows this. If you grew up in the American school system, there is a 99 percent chance that you have been under a system of history instruction that concerns itself primarily (and sometimes exclusively) with an important but narrow group of American people. Your education most likely focused your attention on the American state and some of the most powerful and wealthy people that created it. Widening that focus, including the narratives, perspectives, and lives of all the other Americans who lived under that state is how we get more context. It’s how we learn what we do not know. And it is the best way to understand our present.

“My viewpoint, in telling the history of the United States, is different: that we must not accept the memory of states as our own. Nations are not communities and never have been. The history of any country, presented as the history of a family, conceals fierce conflicts of interest (sometimes exploding, most often repressed) between conquerors and conquered, masters and slaves, capitalists and workers, dominators and dominated in race and sex. And in such a world of conflict, a world of victims and executioners, it is the job of thinking people, as Albert Camus suggested, not to be on the side of the executioners.”

― Howard Zinn, A People's History of the United States

In the last dispatch, we learned about James Loewen and established that American history is less about demigods and demons, and more about people just like us. Howard Zinn’s work does what Loewen wants on so many levels: It gives an overall history of the people. It’s easy to understand, and the chapters are clear and concise ( you can thank Roslyn Shechter, his wife, and a helpful volunteer editor for that). I hope in reading this book you can be inspired to form your own opinions and questions about how we live and why.

You can purchase Zinn’s A People History Of The United States here, at your local bookstore, or find it at a public library. The website in his memorial can point you to his other writings, the Black women he taught who went on to change the world (literally), and his plays. You can learn more about his personal beliefs, the history that haunted him, and his biography.

P.S. Because I care about you, here’s the trailer of Armando Iannucci”s A PERSONAL HISTORY OF DAVID COPPERFIELD. You are very welcome.