You Should Read "Lies My Teacher Told Me"

James Loewen's antidote to despair and boredom caused by typical history classes. It's funny, intelligent, and hopeful.

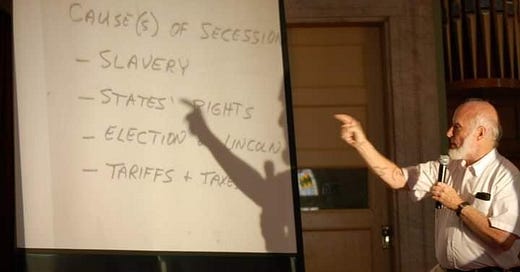

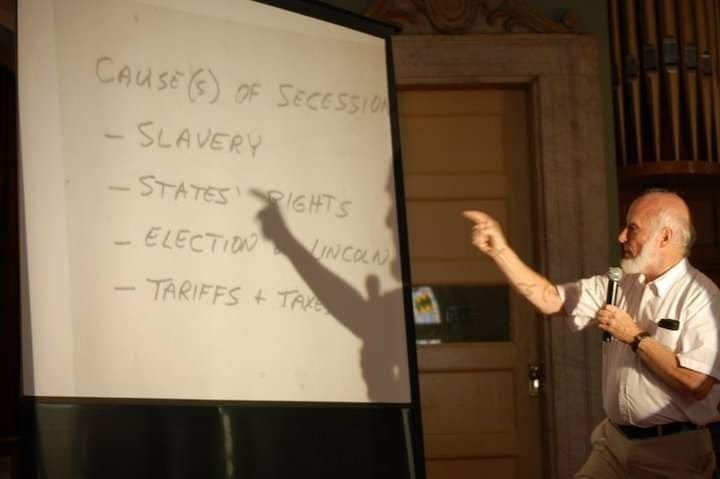

(James Loewen, photo shared

Rodney Hurst. )

I think most of us would agree that the most exciting question that comes after an invitation to a ball (or any very nice party) is What will I wear? Running to the closet, flinging clothes about weeks in advance, weighing the options with excitement. In my young life, I’ve deeply appreciated the events I’ve been able to attend to enjoy a night of glitter, good food, and time off. Who wouldn’t?

Maybe that’s what the educational organizer of the Antebellum Ball thought when she called my Black mother to extend an invitation to her and three of her Black children. Based on my research of these sorts of events staged for students (of all educational types), Antebellum and Confederate Balls -specifically- were all the rage. I think nostalgia dies hard. There are all sorts of reasons we might fix upon a period and long for it. The outfits. The culture. The food. The entertainment. The social and political norms. The things many of us might long for, like a hairstyle or handwritten letter, can be replicated today somewhat painlessly. They don’t require us to subject ourselves to the less palatable aspects of life in the medieval ages or the instability of some revolution. This theoretical time travel or return might only be worth something as important as a relationship, perhaps with another person. Maybe we admire how people related to each other back then, the ways they gathered or organized themselves.

I remember the hopeful words on a faded T-shirt one of my fellow co-op students would often wear. The South Will Rise Again. My mom asked him once what it meant. He didn’t have an answer. He couldn’t tell us what our relationship with him would be in the restored South. What were we rising to? What would return?

My mother is not an American. She also wasn’t any kind of expert on African American or Civil War or Confederate history. I tell myself that maybe she just thought about the event with more sensitivity for five minutes longer than the organizer. That also might be too generous. This event was supposed to be a fun way to learn about that period and time travel for an evening. Great pains were being taken to make sure that the outfits, the food, the dances, and the social rules of the time would be period-appropriate and accurate.

Up to a point of course. My mother wasn’t aware of where that point was though. So she asked the question most of the mothers enlisted to bring this Antebellum dream to life were asking: What shall my children wear?

But my mother didn’t look like any of the other mothers. And the organizer knew this. So that universal question quickly became a particular one.

My mother looked like the kind of person who would have been forced to work the ball. Like the kind of people who would have broken their whip-scarred backs to plant, harvest, and cook the party food. Her children looked like the people who would work inside the house the ball was hosted at, getting the children believed to be “white” ready. The kind of people “graced” with the gentler house tasks because their fathers (believed to be white) owned them and forcibly conceived them out of rape.

What do you want my children to wear? My mother asked. The organizer scoffed. My mother then asked if sackcloth, fuzzy hair, and dirt smears would be appropriate. Should they serve the food? She asked. What gentlemen would be allowed in that period to dance with my daughters? Should I bring them to sit on the floor?

Incredibly, these reasonable questions were met with unreasonable fury. It’s the same fury we are seeing go viral in town halls and at school boards all across the country right now. Recognizable, old fury, desperate in an attempt to convince everyone that no one needs to remember the past accurately. Fury, because remembering the whole truth about American racism and race relations will make our children feel bad. It’s a fury that blinds, where parents stand up and argue in circles against guilt trips that no one intended and defends a past that never existed.

The Antebellum Ball organizer taught history in our homeschool organization. So she decided to educate my mother, starting with what her grandparents had taught her parents, and what her parents had taught her. Slaves were well-taken care of! The slaves in my family loved our family! It’s a lie that all the slaves were unhappy and treated badly! They needed help and the slave owners helped them from starvation and poverty! Slavery was a necessary institution that helped EVERYONE! How would we have fared as a civilization?

The organizer laughed. “I just hate when people don’t know their history”

Perhaps it is too easy (and cruel) to laugh at the stupidity offered up by various flavors of Karens. Taking a potshot at someone who can be written off as a barefoot and pregnant “Becky” (with the good hair) would be, too. We might be tempted to ask what a “backwoods” homeschool mom would know anyway, of historical analysis and slavery? To shape the Floridians in my life who argue for an easily disputed account of history or who make racist assumptions because they swim in an ignorance so all-encompassing--to shape these people into caricatures and lost causes would be wrong. Maybe their perspective isn’t malicious; maybe, even after all this time ignorance is a kind of bliss that’s hard to give up. And in the organizer’s case, perhaps this was just an unfortunate ignorance.

I used to believe that. But ignorance can be unfortunate and calculated at the same time. Nostalgia’s power lies in cultivation. Nostalgia is inherited.

In the bestseller, Lies My Teacher Told Me, the sociologist and historian James Loewen examines the narrative choices that have been made over and over again by historians, teachers, and textbook writers to edit, frame, and assemble our American history. With careful research and many examples, Loewen shatters a careful illusion of neutrality. He credibly demonstrates how many textbook authors continue to make choices that center one ethnicity and their perspective over all others. He shows how the very conflict and ideas that powered policy and legislation get ironed out. He examines how fallible men are transformed into American demi-gods, their actions always ensuring 400 years of unbroken American progress. Loewen is concerned with a tendency that prioritizes feel-good history over the transcendent and troubling truth of a nation. He, too, is concerned with what we cultivate.

“The antidote to feel-good history is not feel-bad history but honest and inclusive history.” - James Loewen

Sometimes I wonder if the ball organizers simply wanted to refrain - as other textbook writers claim- from laying down retroactive moral judgments on the actions of the dead. We want to be fair, we don’t want to hold people to our standards. But this illusion of neutrality, this reticence to cast a judgment, shatters when we consider the ways we the living enshrine our ancestors every year. We make a choice with each holiday and person we choose to unquestioningly celebrate. Is it not a moral judgment to solely honor Columbus over the indigenous women he sold into sex slavery? Is it not a moral judgment when we decide which soldier from which side of some war to cast in bronze? On the 4th of July we light up the sky in honor of a groundbreaking document that was wholly and solely concerned with the property of white, rich men, that rendered poor white men, women, slaves, and Native people politically powerless. We gather around a feast every November to remember a version of a feast that objectively did not happen, to remind ourselves that we have much to be thankful for. We celebrate Black History Month and have days named for American Women and we solemnly remember American citizens who belatedly forced the hands of men to include them in the pursuit of liberty and happiness. We choose, every single year, how we remember our brilliant and brutal and complicated past. We trim. We edit. We focus on some over others. We correct this sometimes. We ignore this with others. Pageant and mythology are not beneath us. Casting moral judgments about the past isn't either.

James Loewen’s Lies My Teacher Told Me is about how we can understand and learn from a complicated and complex past made up of humans just like us. Lowen is not suggesting we only celebrate perfect people or perfect nations. He’s asking us to lay down the myth of perfectionism in its entirety, to grapple instead with a history of humanity. Loewen believed that the truth of what we did, who we were, what we said, and how we built a place mattered. Because that truth first built this country, not the latter myth to bolster nationalism and good feels. That history is complicated, but it’s the only history (and conversation) that accurately shapes the future.

Still, for some reason, we don’t want to hold people to our standards. But why do we make them demigods? Why do we ignore what is right in front of us? Why do we hide the ways - for example -that Thomas Jefferson hid the truth of the free labor that brought dinner to his guests? Why did the instruments of torture and the horrid little shacks these demigods used to subdue other human beings with (the enslaved) disappear on so many plantations? Did they know they were repugnant? Did ears go deaf and eyes go blind to the pain that they had to have seen in the eyes of their wives? In the people that they bought and whipped and assaulted and branded? Why do we pretend our people were creatures too stupid to empathize with other human beings for five minutes or too divine to err from the manifest destiny of American progress? Which is it, America? Are we the children of gods or animals?

James Loewen says neither. We are the children of men. We inherit everything. The promise and the pain. The ways they failed and the ways they triumphed. The beautiful antebellum dances and the slave chains. The fantastic works of liberation and the brutal legislation that rendered some people 2/3s of a human.

“Most textbook authors protect us from a racist Lincoln. By doing so, they diminish students' capacity to recognize racism as a force in American life. For if Lincoln could be racist, then so might the rest of us be. And if Lincoln could transcend racism, as he did on occasion, then so might the rest of us.”

― James W. Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong

Loewen believes that a commitment to inclusive history would bring the history classroom (and country) back into a lively debate, one he says “informed by evidence and reason”. He encourages us to question who is centered in historical narratives and to look at one event from many perspectives. He wants us to identify with the people of a past in a way that acknowledges the truth of their humanity. And you know what? He just hates it when people don't know their history.

Loewen died this August at the age of 79 after a long career inspired by the history he encountered. He was committed to telling the stories of our past and working on a deeply local level to use that past to transform the future. He knew that lies of any kind were toxic, blinding us to what was and what could be. He was (and is still through his writing) a true educator. I hope that in reading Lies My Teacher Told Me you get a sense that the accuracy of ideas can either cripple our textbooks or liberate the American story to be everything it was. You’ll get an idea as to how to engage with our past reasonably and honestly. The website linked here is a fantastic resource to engage with the many different books, stories, and interactive media that made up the body of James Loewen’s work. Loewen was fascinated by America and the people who made it up. This fascination and curiosity are infectious, and you will enjoy the humor and brilliance of his writing and research.

We didn’t end up going to the Antebellum Ball that year. My mom instead purchased a copy of Lies My Teacher Told Me. It sat around for years. That same copy inspired and informed this project. Ultimately, I discovered that more than hating that people didn’t know their history, James Loewen loved who we could be when we knew it.